Sobre Mathigon

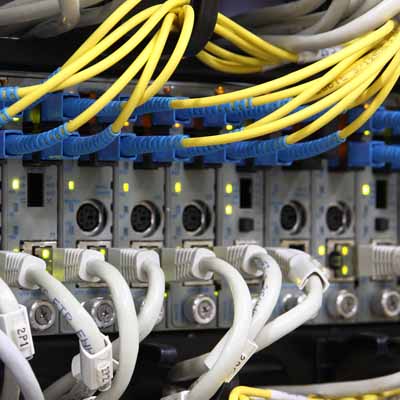

Everything in our world follows mathematical laws: from the motion of stars and galaxies to the transmission of phone signals, bus timetables, weather prediction and online banking. Mathematics lets us describe and explain all of these examples, and can reveal profound truths about their underlying patterns.

Unfortunately the school curriculum often fails to convey the incredible power and great beauty of mathematics. In most cases, school mathematics is simply about memorising abstract concepts: a teacher (or a video, or a mobile app) explains how to solve a specific kind of problem, students have to remember it, and then use it to solve homework or exam questions. This has changed very little during the last century, and is one of the reasons why so many students dislike mathematics.

“It is a miracle that curiosity survives formal education.”

– Albert Einstein

In fact, the process of studying mathematics is often much more important than the actual content: it teaches problem solving, logical reasoning, generalising and abstraction. Mathematics should be about creativity, curiosity, surprise and imagination – not memorising and rote learning.

Mathigon is part interactive textbook and part virtual personal tutor. Using cutting-edge technology and an innovative new curriculum, we want to make learning mathematics more active, personalised and fun.

Active Learning

Rather than telling students how to solve new kinds of problems, we want them to be able to explore and “discover” solutions on their own. Our content is split into many small sections, and students have to actively participate at every step before the next one is revealed: by solving problems, exploring simulations, finding patterns and drawing conclusions.

We built many new types of interactive components, which go far beyond simple multiple choice questions or textboxes. Students can draw paths across bridges in Königsberg, run large probability simulations, investigate which shapes can be used to create tessellations, and much more.

Personalisation

As users interact with Mathigon, we can slowly build up an internal model of how well they know different related concepts in mathematics: the knowledge graph. This data can then be used to adapt and personalise the content – we can predict where students might struggle because they haven’t mastered all the prerequisites, or switch between different explanations based on students’ preferred learning style.

A virtual personal tutor guides you step-by-step through explanations and gives tailored hints or encouragement in a conversational interface. Students can even ask their own questions.

Storytelling

Using Mathigon requires much more effort and concentration from students, compared to simply watching a video or listening to a teacher. That’s why it is important make the content as fun and engaging as possible.

Mathigon is filled with colourful illustrations, and every course has a captivating narrative. Rather than teaching mathematics as a collection of abstract facts and exercises, we use real life applications, puzzles, historic context, inter-disciplinary connections, or even fictional stories to make the content come alive. This gives students a clear reason why what they learn is useful, and makes the content itself much more memorable.

All these goals are difficult to achieve in a classroom, because a single teacher simply can’t offer the individual support required by every student. Of course, we don’t want to replace schools or teachers. Mathigon should be used as a supplement: by students who are struggling and need additional help, students who want to go beyond what they learn at school, or even by teachers in a blended learning environment.

The ideas of active learning and personalised education are nothing new – teachers and researchers have been experimenting and writing about it for many years. Mathigon is one of the first implementations on a fully digital platform, which means that we can reach a much larger number of students. Of course, we are just getting started and there is still a long way to go.

One of the key underlying concepts is constructivism, the belief that students need to “construct” their own mental models of the world, through independent exploration, discovery and project-based learning. Constructionism was first developed by psychologist Jean Piaget (1896 – 1980), and then extended by mathematician, computer scientist and educator Seymour Papert (1928 – 2016).

There is plenty of research and evidence supporting this approach to teaching mathematics, and many existing ideas or examples we use as inspiration:

What Makes People Engage With Math – TED Talk

Grant Sanderson, 3blue1brown (2020)

Numbers at play: dynamic toys make the invisible visible

Scott Farrar, May-Li Khoe, Andy Matuschak (2017)

The 2 Sigma problem: The Search for Methods of Group Instruction as Effective One-to-One Tutoring

Benjamin Bloom (1984)

Do schools kill creativity? – TED Talk

Ken Robinson (2006)

Media for Thinking the Unthinkable

Bret Victor (2013)

Essays

The Value of Teaching Mathematics

Mathematics Outreach and Popularisation

Content and Engineering

Philipp Legner

Philipp studied mathematics at Cambridge University, and mathematics education at the UCL Institute of Education in London. He founded Mathigon while volunteering with outreach projects in Cambridge.

Previously, Philipp worked as software engineer at Google, Bloomberg, Wolfram Research and Goldman Sachs. He consults for educational organisations like MoMath and IMAGINARY, and regularly speaks at conferences all around the world.

David Poras

David studied mathematics at Vassar College and education at the University of Massachusetts. He is a middle school math teacher at Weston Middle School in Weston, MA. In his 20+ years at the school, David has held a variety of leadership roles. In 2017, he was a runner-up for the Rosenthal Prize for Innovation and Inspiration in Math Teaching awarded by MoMath.

Eda Aydemir

Eda studied mathematics education at Bogazici University and has master’s degrees in Educational Supervision and Instructional Design. She has been teaching mathematics since 2003 and has been organizing Math Events, Exhibitions, and Math Weeks since. Eda has also spoken at several educational conferences in Turkey, and she is writing about math education at funmathfan.com.

Advisory Board

Cindy Lawrence

Cindy is the Executive Director and CEO of MoMath, the National Museum of Mathematics in New York City, where she works to change public perceptions of mathematics.

Conrad Wolfram

Conrad is the co-founder and CEO of Wolfram Research Europe, the makers of Mathematica and Wolfram|Alpha. He also founded the Computer-Based Math Project, to reform maths education.

James Tanton

James is the founder of Global Math Week and mathematician-at-large for the Mathematical Association of America. He is committed to sharing the delight and beauty of the subject.

Rich Miner

Rich is a co-founder of Android, partner at Google Ventures, and director at Google, where he works on new products for students and teachers.

Sarah Lee

Sarah is a former startup founder with over 16 years of experience scaling exceptional education programs and schools, and coaching founding teams of EdTech Startups globally.

Simon Singh

Simon is the author of bestselling books like “Fermat’s Last Theorem”, “The Code Book” and “The Simpsons and Their Mathematical Secrets”, and founder of the charity Good Thinking.

Translations

- Arabic: Jad Succari

- Catalan: David Virgili

- Chinese: iuway, Kaka, jexchan

- German: Harald March

- Italian: Michela Riganti, Letizia Diamante, Antonio La Barba

- Portuguese: Hugo Tadashi

- Romanian: Claudia Dumitrascu, Ariana-Stanca Vacaretu

- Russian: Аня Никитина

- Spanish: Scott Nepple, Héctor Palacios, Carlos Ponce Campuzano, Pilar Fortuny Ayuso

- Turkish: Utku Aytaç, Can Ozan Oğuz, Ebru Nayir, Murat Uyar, Buket Eren, Eda Aydemir, Begüm Gülşah Çaktı, Ayşe Yiltekin, İsmail Kara

- Vietnamese: Ngo Thuy Anh Tuyet

Volunteers and Supporters

We want to thank all these volunteers and supporters for their contributions, advice, proofreading, feedback or generous donations:

- Justin Baron

- Srikanth Chekuri

- Alison Clark-Wilson

- Dirk Eisner

- Susan Jobson

- Tim Knight

- Michal Kosmulski

- Wolfgang Laun

- Joel Lord

- Rose Luckin

- Samantha Marion

- Alex McCall

- Manuel Menzella

- Huw Mort

- Meenakshi Mukerji

- Andy Norton

- William O’Connell

- Antonella Perucca

- Anwit Roy

- Kostas Symeonidis

- Andre Wiederkehr

- Danny Yee

- Arul Kolla

- John Green

- Yi-Hsuan Lin

- Samuel Watson

- Enrico Poli

- Zach Geis

- Jack Kutilek

- leeyeewah

- Leif Cussen

- Chris Peel

- Sergei Kukhariev

- Alexander Shapoval

- Andrea Michi

- Troy Weets

- 安強 朱

- Howard Mullings

- Oleksandr Prokopenko

- Evgeny Sushko

- Israel Parancan Navarro

- Josep lluis Mata

- Valeri Jean-Pierre

- Alex Munger

- Jay Mitchell

- Denis Zuev

- Matematika Tivat

- Nafez Al Dakkak

- Amy Dai

- Clara Marx

- Kimberly Lilly

- Angela Bottaro

- Yolanda Campos

- rittersg

- Tom Leys

- Anuj More

- Srini Kadamati

- Howard Lewis Ship

- Leo

- Becca LeCompte

- Reymund Gonowon

- Axek Brisse

- Dev Karan Ahuja

- Guillaume

- Antony Mativos

- Bryan Shull

- Matthew Deren

- Razmik Badalyan

- Georgreen Mamboleo

- Yijia Wang

- Devin Wilson

- billxiong

- dacapo

- Cyril Ghys

- charlespipin

Nueve principios Para un gran contenido matemático

1. El aprendizaje debe inspirar

Las matemáticas deberían inspirar y empoderar a los estudiantes, no asustarlos ni confundirlos. Deberíamos mostrar la sorprendente belleza y el gran poder de las matemáticas y que todo el mundo puede "hacer matemáticas".

2. Cuenta una historia

La narración puede motivar a los estudiantes, hacer que el contenido sea más memorable y justificar por qué lo que se está aprendiendo es importante, incluidas aplicaciones de la vida real, acertijos curiosos o antecedentes históricos. Más…

2. Cuenta una historia

En lugar de presentar las matemáticas como una colección abstracta de resultados, debemos presentar cada tema nuevo con una narrativa interesante que muestre a los estudiantes por qué lo que están a punto de aprender es útil y vale la pena hacerlo. Esto no solo es más interesante y motivador, sino que también hace que el contenido sea mucho más memorable.

Las historias pueden basarse en aplicaciones de la vida real ("predecir el clima"), eventos históricos ("medir la altura del Monte Everest"), un rompecabezas matemático ("que da forma a un mosaico") o incluso personajes de ficción. Incluso podría haber algo de suspenso y giros en la trama, donde los estudiantes inicialmente no saben a dónde podría conducir la historia y luego se sorprenden con un resultado matemático inesperado.

3. Exploración y creatividad

Permite que los estudiantes exploren, sean creativos, cometan errores, practiquen el pensamiento crítico y descubran nuevas ideas, en lugar de simplemente decirles los resultados finales y los procedimientos para memorizar.

4. Las matemáticas están en todas partes

Siempre estamos rodeados de patrones y relaciones matemáticas. Los estudiantes deben ser capaces de reconocerlos y aprovechar el poder de las matemáticas para resolver problemas de la vida diaria.

5. No es útil, pero tiene sentido

No todos los temas del plan de estudios tienen que ser útiles en la vida cotidiana (ni Mozart ni Shakespeare), pero todos los temas deben ser significativos, debido a sus aplicaciones o significado matemático. Más…

5. No es útil, pero tiene sentido

Una gran parte de las matemáticas que los estudiantes aprenden en la escuela no serán útiles en la vida cotidiana, incluso si terminan trabajando como científicos o ingenieros de software. Y eso está bien, como hemos visto en el principio 3, una de las razones para estudiar matemáticas es aprender habilidades transferibles como la resolución de problemas y el pensamiento crítico. Hay muchas otras materias en la escuela que tampoco son "útiles", desde los Sonetos de Shakespeare hasta las Sinfonías de Mozart, e incluso las leyes del movimiento de Newton. En cambio, estos temas nos hablan de cultura e historia, o nos ayudan a comprender y dar sentido al mundo que nos rodea.

Sin embargo, gran parte del plan de estudios de matemáticas existente tampoco es significativo, y eso es un problema. En lugar de enseñar sobre temas aburridos y esencialmente sin sentido como la división larga, la racionalización de denominadores o pruebas de geometría de dos columnas, deberíamos enseñar sobre redes, caos, ciencia de datos, criptografía o teoría de juegos: temas que son emocionantes y hermosos, y que tienen un impacto directo en todas nuestras vidas. Estos temas pueden ayudar a los estudiantes a comprender mejor el mundo en el que vivimos, incluso si no son directamente útiles en la vida cotidiana.

6. Las matemáticas son visuales

Las ecuaciones son útiles, pero a menudo hay representaciones mucho mejores de conceptos y relaciones matemáticos. El contenido debe ser lo más visual y colorido posible.

7. Intuición sobre rigor o fluidez

El rigor es una parte importante de las matemáticas, y también hay un lugar para practicar la fluidez, pero el objetivo principal debe ser desarrollar la intuición, la comprensión profunda y la aritmética general. Más…

7. Intuición sobre rigor o fluidez

Cuando los matemáticos piensan en su tema, pueden asociar principalmente el rigor y la formalidad de las pruebas. Cuando los estudiantes de secundaria piensan en matemáticas, pueden asociar problemas de fluidez al prepararse para los exámenes. En realidad, ninguno de estos dos enfoques es lo que necesitamos de las matemáticas escolares.

El enfoque debe estar mucho más en la intuición y la comprensión matemática: estimar la respuesta a problemas o verificar una respuesta existente, reconocer y generalizar patrones, derivar procedimientos y ecuaciones que no se recuerden exactamente y ser conscientes de errores y conceptos erróneos comunes (especialmente en temas como probabilidad y estadística).

Muchos conceptos matemáticos tienen una amplia gama de representaciones diferentes (por ejemplo, fracciones como áreas sombreadas, decimales, porcentajes, grupos o tasas). Los estudiantes deben estar familiarizados con tantas representaciones como sea posible, comprender sus relaciones y poder decidir cuál es la más adecuada para un problema específico.

8. Discusión y trabajo en equipo

Las matemáticas rara vez son una actividad solitaria y muchos problemas reales no tienen una única respuesta correcta. Las discusiones, la colaboración y el trabajo en equipo deben ser una parte clave de todo plan de estudios.

9. Las matemáticas están vivas

Para hacer que las matemáticas sean más relevantes, es importante retratar su historia, descubrimientos recientes e investigación actual, así como los diversos grupos de matemáticos y científicos que realizan este trabajo.